One form of community organizing involves local citizens in collective action focused on issue. Issues emerge from tensions and contentions. They reflect the dissatisfaction or anger felt by local residents.

Often, “citizen participation” is used to indicate the number of dissatisfied people who act in public to resolve an issue. However, the number of people participating depends upon how many are strongly dissatisfied or very angry. Among this select number of people, there are many who are disaffected but unwilling to act in public. Therefore, “citizen participation” about most issues is necessarily limited to those who are both dissatisfied and are also willing to act in public arenas.*

There is another approach to community organizing that seeks participation on the basis of a citizen’s desire to contribute to the common good. Their motive for engaging is not about contention or issues. It is about their desire to share their own capacities for the common good.

In this form of organizing, the collective participation is based upon the identification and mobilization of the community building and problem-solving capacities of local residents and the associations they create to achieve the common good.

In this form of organizing, some neighbors visit each household on their block to find out which gifts, skills, interests and knowledge their neighbors value about themselves. Then they are asked whether they would be willing to share these capacities with their neighbors and/or their neighbor’s children.

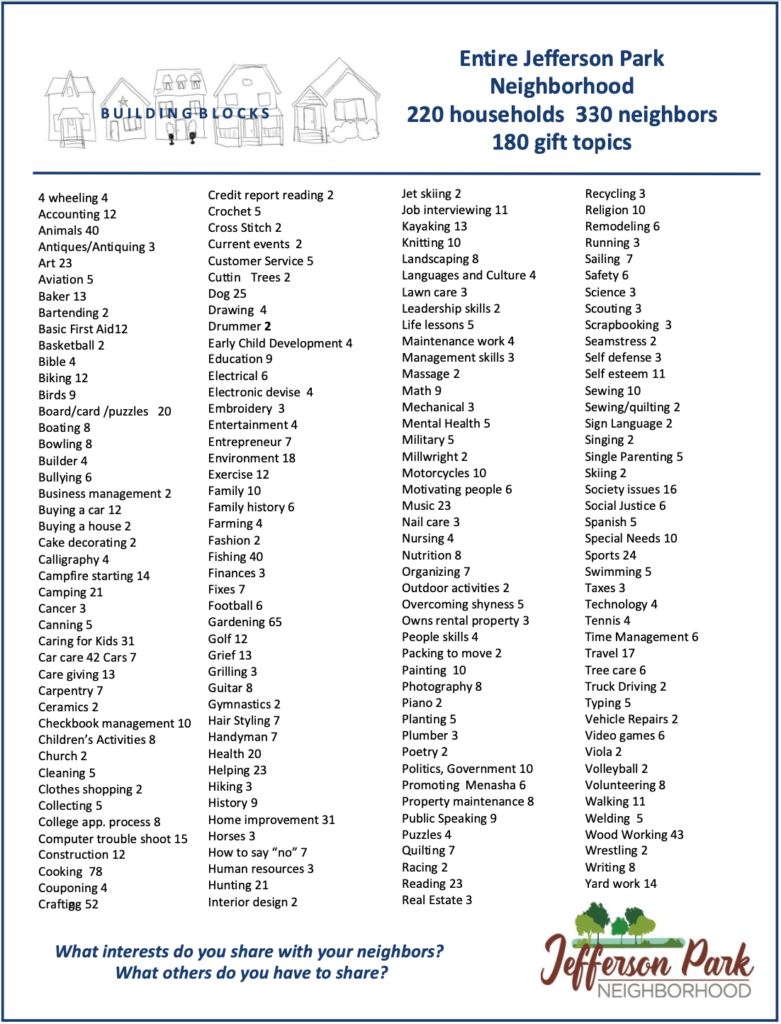

One indication of the nature of local citizen capacities is the following “capacity inventory” completed on 20 blocks of the Jefferson Park neighborhood in Menasha, WI.

This table demonstrates both the number and nature of the neighbors with capacities they are willing to share. The numeric potential for participation and action around these capacities is much greater than the parallel issue-oriented inventories.

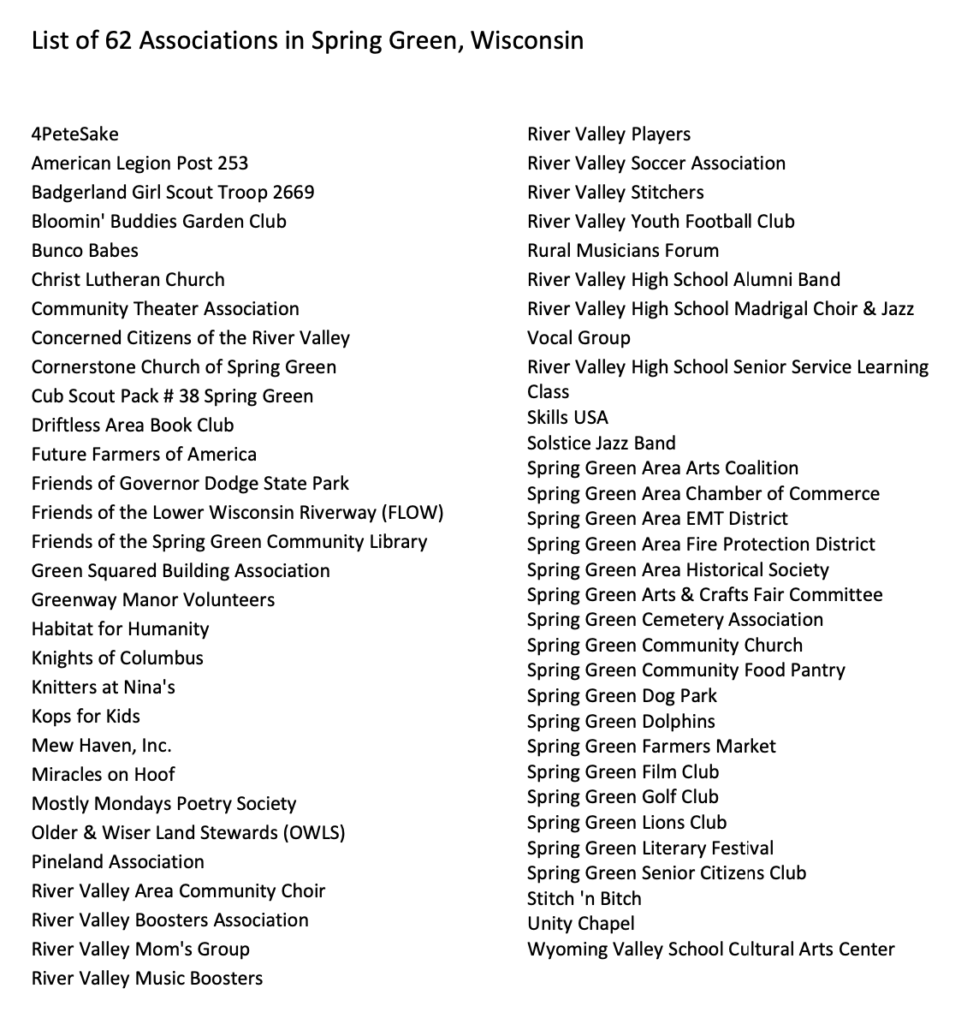

The capacity-oriented organizing has a second kind of civic engagement that it incorporates. These are the clubs, churches, organizations, groups and associations to which the local residents belong. These groups are usually smaller, face-to-face associations where the members do the work and they are not paid. They are the infrastructure for local engagement. An example of this infrastructure is the inventory of civic engagement among the associations in the rural community of Spring Green, WI. There, a group of residents found the following 62 associations with names. (This list does not include the numerous informal associations that do not have public names).

When the small local research group had completed conducting this inventory, one member observed, “I never realized all these groups are here. Once you see them all you realize that if they disappeared our town would die.”

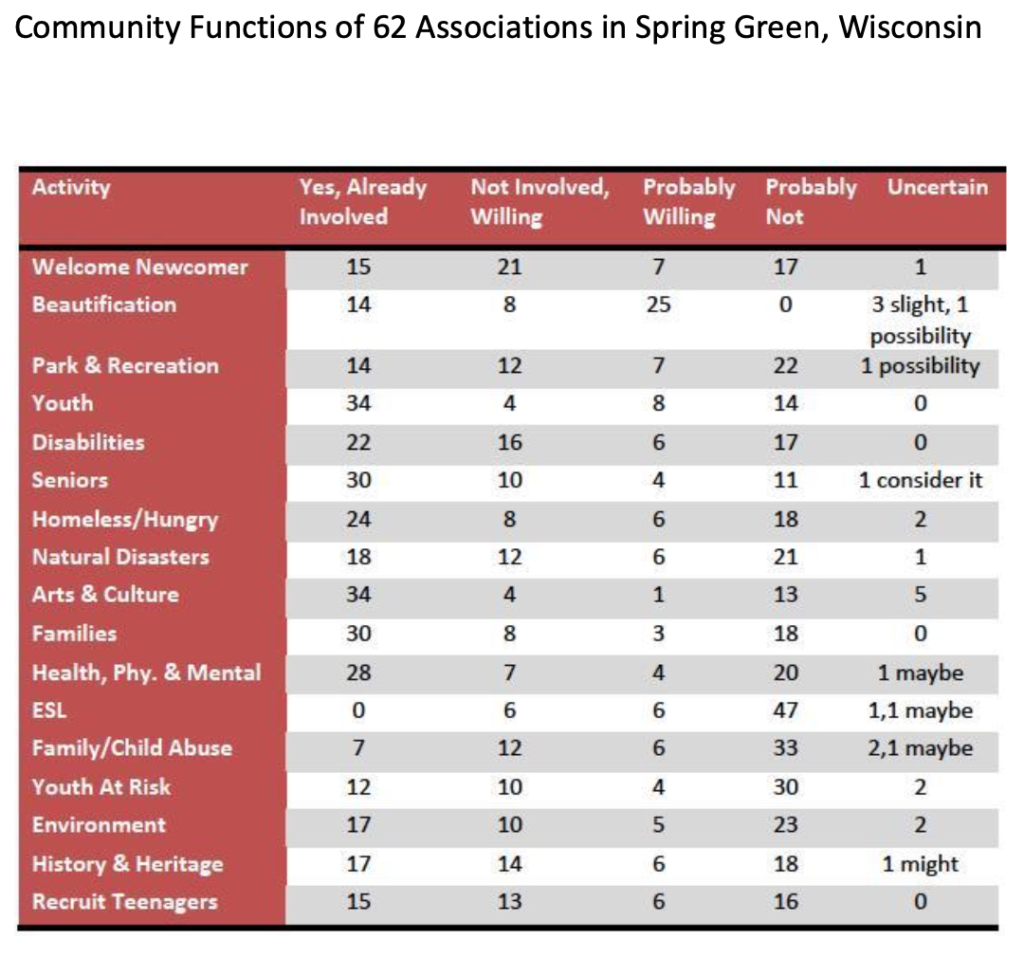

Once this associational inventory was completed, the group interviewed the chair of each association. One set of the questions they asked involved showing the chairperson a list of civic functions that some associations perform. The following table shows a list of those functions. The associational leaders were asked which functions their group performed and which functions they would perform if asked.

This community-based research indicates that there is great potential for wide-spread increases in civic engagement if the focus is on individual contributions and the associations those individuals create.

If we want to have much more citizen participation, the local residents and their associations need to be invited to contribute what they have that they value. Practically speaking, this invitation needs activating residents who take on two functions.

The first is the role of a connector. These are residents who identify the capacities of their neighbors and see the multiple possibilities of new productive activities when they are connected.

The second activator is the role of “precipitator” – neighbors who invite and connect the associations to undertake the new functions they have said they would participate in.

In every neighborhood, there are many people who have these connecting and precipitating skills. The basic community building and power creating practice is engaging and supporting local residents who will intentionally take on these functions.

A detailed guide to initiating these forms of creating widespread civic participation can be found in the publications of the ABCD institute at abcdinstitute.org. See Publications on Associations and Connecting Assets.

Finally, there is much current concern about the polarization among U.S. citizens. However, it is these same “polarized” people who are prepared to share with their neighbors in behalf of the common good. The positive possibility for America is to promote the sharing of capacities. This shared experience is critical in renewing our ability to see the value in each other and reasserting our power to create and problem solve together.

* This is not to say that this form of issue advocacy is not important. However, for the reasons indicated it is, by its nature, limited in the number of neighborhood people actually participating.

Going Further:

- The Neighborhood is the Center (Harges, Block, McKnight)

- A Study of the Benefits Provided by Local Associations (McKnight)

- Keys to Broad and Inclusive Participation (Diers)