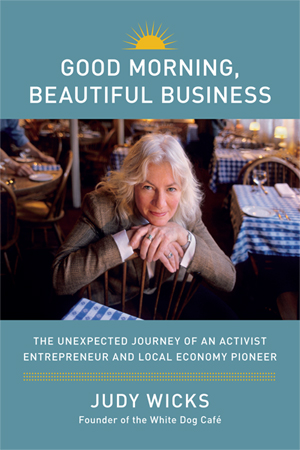

A few years after Judy Wicks opened the White Dog Cafe in West Philadelphia, she hung a sign in her bedroom closet as a daily reminder of what her business could be if she gave it creativity and care. Two decades after its humble beginnings, Wicks’ restaurant had become a model for socially responsible business, and Wicks herself was a national leader of the movement for local, living economies.

The message on that sign, “Good morning, beautiful business,” is also the title of Wicks’ memoir, the story of a woman driven by a love of community, a strong sense of justice, and a taste for adventure.

Wicks worked for VISTA in a remote native village in Alaska, laid down in front of a bulldozer to stop the demolition of a historic building, grew one of the most socially responsible businesses in the nation, and co-founded several sustainable business organizations. She also threw some fabulous parties. The courage, creativity, and sense of fun in her story are contagious.

Growing up in the 1950s, Wicks shunned the stereotypes of how girls should behave and longed to play baseball with the boys. But when, almost by accident, she became a businesswoman and entrepreneur, she recognized that her feminine desire to nurture was an asset in bringing collaboration to business and creating a more caring economy.

In the early days of the White Dog Cafe, located in the downstairs of Wicks’ Victorian brownstone, she couldn’t afford to build a commercial kitchen or hire a chef. She cooked the restaurant’s meals in her own kitchen while she watched her young son and daughter, and customers tromped upstairs to use the family’s bathroom. Eventually the restaurant filled three row houses, a companion retail store filled two more, and her businesses were grossing $5 million annually.

But Wicks wasn’t content to do well; she wanted to do good. Before most Americans had heard of farm-to-table, Wicks bought her ingredients from local farms and breweries. When she read about factory farming, she switched to humane sources for the restaurant’s meat. Then she created Fair Food, a humane farm network and free consulting program to teach her competitors about the importance of using humanely sourced meat.

Wicks also used her business as a platform for social and political activism. She traveled to Nicaragua, Vietnam, the Soviet Union, Mexico, and Cuba to establish sister restaurants and build friendships in parts of the world where she felt U.S. foreign policy was doing harm. She held “Table Talks” and published a newsletter to inform her customers about her trips as well as other peace and justice issues.

“‘Food, fun, and social activism’ became the White Dog motto,” writes Wicks, who attributes many of her socially responsible business decisions to living above her restaurant. “When we live and do business in the same community, reconnecting home life and work life, we are more likely to run businesses in the best interest of the community we care about.”

When we live and do business in the same community, reconnecting home life and work life, we are more likely to run businesses in the best interest of the community we care about.

Wicks paid her employees a living wage, started a mentoring program for the area’s high school students, and made her business the first in Pennsylvania to purchase 100 percent renewable energy. Good Morning, Beautiful Business proves that profit can accompany making the world better. It should be widely read in business schools and entrepreneurial circles, but it offers ample lessons for others as well.

Wicks challenges us to look at how we can make a difference in our daily lives and with our dollars. “You can find a way to make economic exchange one of the most satisfying, meaningful, and loving of human interactions,” she writes. At a time when we hear much about what’s wrong with the economy, Wicks helps us imagine an alternative.

She envisions “a new economy based on smallness” made up of independent businesses and decentralized farms that work cooperatively, invest in each other, and pay attention to a triple bottom line: people, planet, and profit. Through her work at the Social Venture Network, the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE), and other organizations, she has spent decades working to realize this vision.

“We’re out to create a global system of human-scale, interconnected, local, living economies that provide basic needs to all the world’s people,” she writes. “To put it simply, we believe in happiness.”